Has this ever happened to you? You just want to send a present to a friend or relative containing a small bottle of perfume. Yet the carrier looks at it in alarm. “We can’t take this package like this! It may be dangerous goods!” How can a tiny bottle of perfume be dangerous? And if it is, what can you do to get it to your loved one?

Figure 1: Looks innocent!

A common misconception among the public is that consumer items such as cosmetics can’t be dangerous. While modern regulations have gone a long way to eliminating dangerous components that could kill people in the pursuit of the perfect look, such as lead, arsenic, and mercury, many things found today in the beauty business are still classed as dangerous goods for transportation. That means industry must follow all applicable regulations, and consumers must also remember that in certain situations, their personal items might be regulated for transport.

Whether you’re shipping in the United States under the “Hazardous Materials Regulations” of Title 49 of the Code of Federal Regulations (49 CFR), or in Canada under the “Transportation of Dangerous Goods Regulations” (TDG), you must normally be a trained and certified shipper of hazardous materials (USA) or dangerous goods (Canada). That means that your deceptively simple intention to send a gift can bring up unexpected complications.

What Beauty Products are Dangerous?

Most cosmetics and beauty products on the market today are, of course, relatively low hazard. But that doesn’t mean no danger at all. Some of the common beauty products that can be dangerous goods include:

- Fragrances are often based on flammable solvents such as alcohol, making them Class 3, Flammable Liquids, for transport.

- Aerosols – many beauty products come in the form of aerosol sprays. These range from hair spray to spray tanning compounds, and are classed as Class 2, Compressed Gases. (But don’t forget that the “finger pump” sprays aren’t shipped under pressure and won’t fall under this class.)

- Nail polish and polish remover – these usually contain solvents such as acetone and may qualify as Class 3, Flammable Liquids.

- Hair dye – may contain chemicals called “organic peroxides,” which are classified as Class 5.2 under the transport regulations.

- Wipes – many cloth wipes for removing makeup or nail polish are impregnated with flammable solvents. They’ll fall into Class 4.1, Flammable Solids.

- Curling irons with gas cartridges – some curling irons run on propane cartridges rather than outlet power. This puts them into Class 2, Compressed Gases.

For industrial products, it’s usually easy to find out from the supplier if they’re regulated for transport by getting the Safety Data Sheet (or SDS). This document will give important safety information about the product and should state in Section 14 if the product is dangerous goods. The bad news is SDSs are not legally required for cosmetics and most consumer products. The good news is that many suppliers will still provide them on request. If they don’t, most consumer product companies will have a company phone number listed on the packaging for questions. You can call and ask directly if the product must be transported as dangerous goods.

If the answer is “no,” you don’t have a problem. However, the carrier may still want you to verify in writing that the substance has been reviewed and declared non-dangerous.

If the Cosmetic is Dangerous Goods

If the supplier verifies that the product is dangerous, then it becomes more complicated. Let’s say, for example, the SDS says that your product is “Perfumery products, Class 3, UN1266, Packing group II” – in other words, it’s a moderately flammable liquid and definitely dangerous goods. In general, only people specifically trained and certified can prepare dangerous goods and offer them for shipment. If you’re not trained, you’re not legally supposed to try. However, there are some options worth exploring to get your perfume to the waiting receiver.

- Hire someone to do it for you – this can be expensive, but is the safest and surest. Companies called “repackers” are often found around major airports and shipping facilities. They have the training and expertise and can guarantee your perfume is properly packaged, labeled, and documented. But their services will add significantly to the cost of the shipment.

- Order online, and let the vendor worry about it – Instead of buying in a brick-and-mortar store, you may be able to order the product online. Amazon, Walmart, and most other large online vendors have their own dangerous goods programs and can be quite adept at getting hazardous goods to the intended recipient. Some will even provide gift packaging.

- Send a gift card – Yes, sometimes it’s easiest to simply return the product and replace it with a gift card for an equivalent amount. Maybe not quite as heartwarming to receive, but simple and cost-effective. Plus, the receiver can pick the product that best suits them.

But maybe you really want to do it yourself. There are actually some options that would allow untrained people to ship low-risk dangerous goods. However, even if you’re not trained, you will need to understand some specific procedures.

Limited Quantities

If you can arrange for ground-only delivery, this will be an excellent option. Most cosmetics in standard retail sizes are relatively small – in fact, the manufacturers usually pick the sizes with an eye to being able to use the limited quantity provision.

To ship something as a limited quantity, you need to find the maximum size allowed for an inner container. In 49 CFR, this is a rather complicated procedure – first, you need to check the Hazardous Materials Table to find the “Exceptions” section number in Column 8A, then find that section in Part 173 to get the limited quantity size.

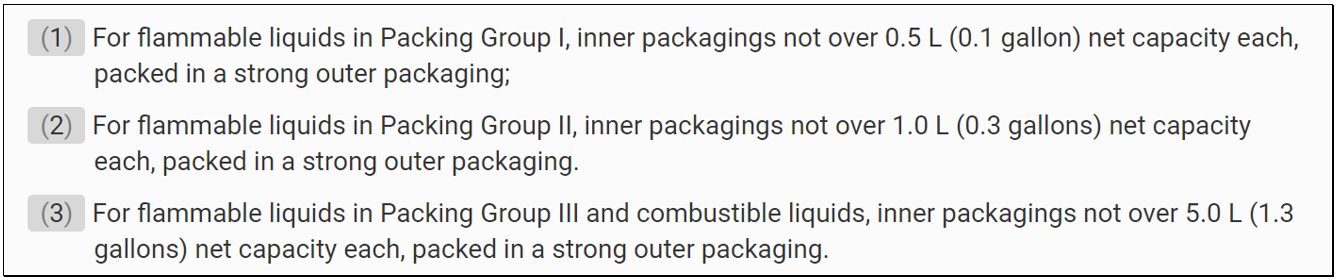

For flammable liquids, like perfume in Class 3, the section code is “150,” so you must go to section 173.150. There, in paragraph (b), you’ll find the size limits for inner containers, based on the packing group:

Since our perfume is in Packing Group II, it means the maximum size for an individual bottle of perfume would be 1 Litre.

However, there’s another complication (but at least it’ll be in your favor here.) In Column 7, there is a Special Provision, with the code number 149. If you look this up in the next section, 172.102, it will explain that for shipments of certain flammable liquids like perfume, the limited quantity inner receptacle size is increased to a whopping 5 Litres per bottle.

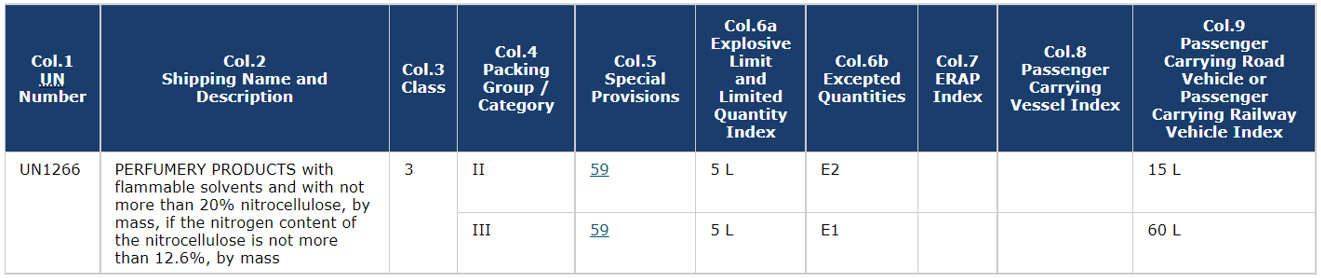

In Canada’s TDG, this is a little easier – you just have to look the product up in Schedule 1, and Column 6a will give you the quantity. It turns out that both regulations have the same limit for UN1266 in Packing Group II – 5 Litres per bottle.

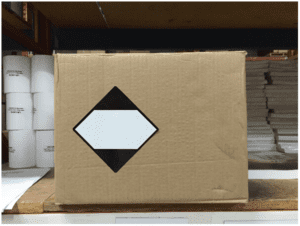

Next, the bottle of perfume must be put in strong outer packaging. This could be a good sturdy shipping fibreboard shipping carton, for example. Inner bottles should be protected so that they won’t spill or leak during normal conditions of handling, but specifics on how exactly to do this are left up to you. Each completed package must not weigh more than 30 kilograms gross, but you can ship multiple packages like this at a time.

Finally, each package must be marked with the Limited Quantity diamond (a black diamond on a contrasting background, with top and bottom corners blacked out.) The standard size is 100 mm (4 inches) per side, but it can be reduced to 50 mm (2 inches) per side to make it fit on smaller packages.

And that’s basically it. Other requirements, including certified packaging, dangerous goods documentation, and placards don’t apply.

Excepted Quantities

There’s another provision that can be used for small containers, although it will be simpler to use the limited quantity provisions in most cases for ground shipments. These are called “excepted quantities.”

This system was originally intended for air shipments, but may be used, with modifications, for ground as well. If you want to prepare your excepted quantity for ground shipment, you can go to either 49 CFR section 173.4a for the U.S. or TDG section 1.17.1 for Canada.

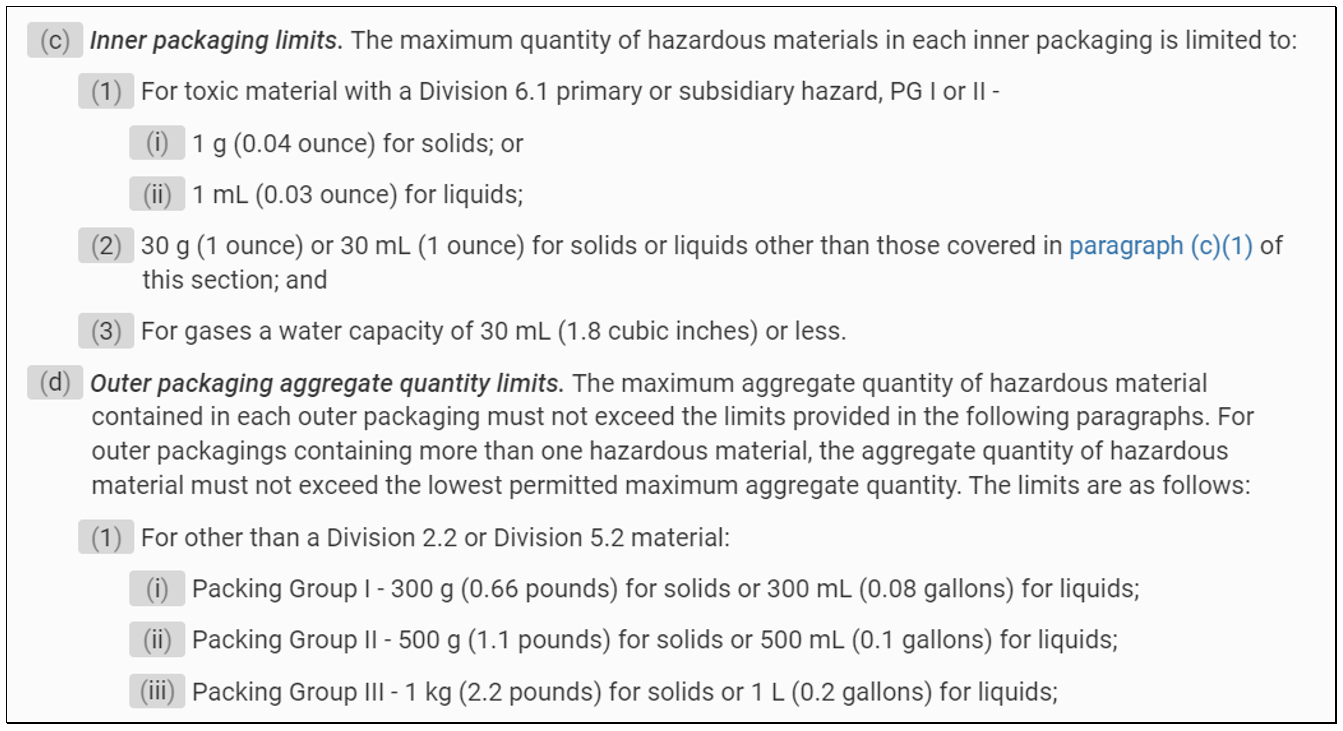

First, you need to find the size limit for your inner packages and the total amount allowed per package. In 49 CFR, this is given in section 173.4a paragraph (c) and (d):

So, we are limited for our perfume, as a Class 3, Packing Group II product to inner bottles no larger than 30 milliliters and a maximum of 500 milliliters per box.

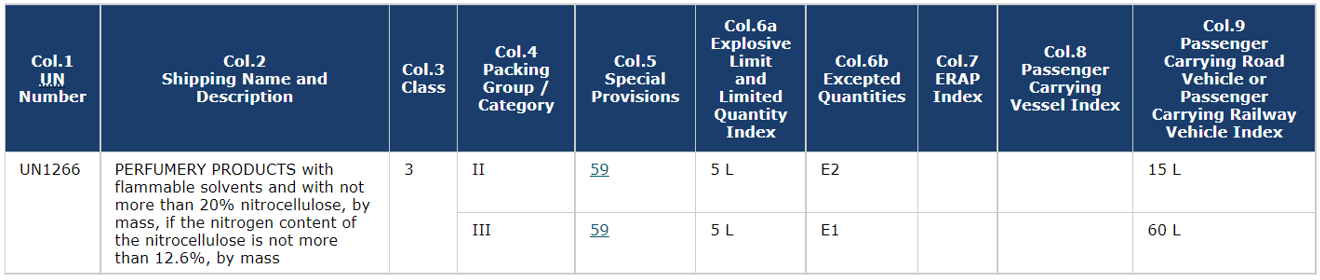

The sizes will usually be the same for Canada, although the method to find them is different. First, you’ll need to go back to Schedule 1 and look up UN1266, Perfumery products. This time, we’ll look at Column 6b, which will give us a code number.

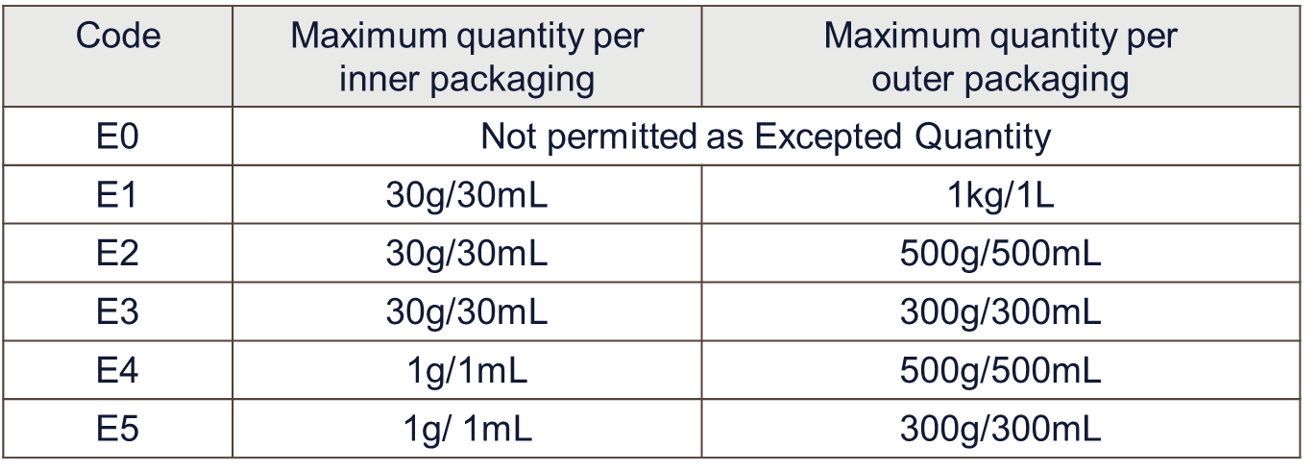

For Perfumery products, Packing Group II, the code number is “E2.” Then, to find what this means, we must go to section 1.17.1, which has a table that explains what these codes mean:

The “E2” code means that inner bottles cannot exceed 30 milliliters of liquid or 30 grams of solid product, and the maximum volume per package is 500 milliliters or 500 grams. There is normally no difference in these values between Canada and the U.S., even if they use very different routes to find them!

Next, we have to assemble the packaging. Follow either 49 CFR or TDG, depending on the country you’re starting in, but the basic procedure will be as follows:

- Seal the inner receptacles well.

- Place them in a leakproof intermediate packaging, such as a plastic bag or metal can, with enough cushioning to protect the receptacles and enough absorbent to soak up any liquid that could leak. The cushioning and absorbent must not react dangerously with the substance being shipped.

- Place the intermediate packaging into a strong, rigid outer packaging such as a sturdy fibreboard box.

- The package should be capable of passing specified drop tests and a stacking test as described in the section you’re using.

Once you’ve put the package together, you must mark it with the Excepted Quantity mark. This requires a red hash-marked border, so simply printing out a black-and-white template won’t be sufficient, and it’s best to purchase a pre-printed one. Under the E symbol, put the class number of your product (for a flammable liquid like perfume, it’s “3”), and under that, put the name of the shipper or recipient.

Once the package has been marked with the excepted quantity symbol, you may ship it by ground without having to fill out a dangerous goods document or otherwise treat it as dangerous goods.

An oddity to watch out for when shipping excepted quantities by ground in Canada is that you are restricted to no more than 1,000 packages of excepted quantities per vehicle. This is not a restriction that applies to limited quantities, even though each limited quantity piece may be significantly larger.

Mailing Cosmetics

If you plan on mailing your cosmetics, rather than using a courier such as UPS or Purolator, it’s not as simple as dropping them in the nearest mailbox.

Canada Post considers “packages that contain dangerous goods or that display dangerous goods symbols” to be “non-mailable matter.” On the other hand, the United States Postal Service (USPS) will take some hazardous materials. Their rules are given in Publication 52, Hazardous, Restricted, and Perishable Mail. The postal staff should be informed when you offer them products that qualify as hazardous.

This sounds like a lot, but once you become familiar with the requirements for limited and excepted quantities, they’re much easier than regular dangerous goods shipments. If you need assistance getting started, contact us here at ICC Compliance Center, 1-888-442-9628 (U.S.) or 1-888-977-4834 (Canada), and ask for one of our Regulatory Experts. We can step you through the basics as well as providing any labeling you might need.

Sources:

“Hazardous Materials Regulations,” Title 49, Code of Federal Regulations, https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-49/subtitle-B/chapter-I/subchapter-C

“Transportation of Dangerous Goods Regulations,” https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/regulations/sor-2001-286/

Cosmetics and Skin, “Aerosol Cosmetics,” https://cosmeticsandskin.com/efe/aerosols.php

Purolator, “Shipping Dangerous Goods – Limited Quantity Exemption,” https://www.purolator.com/en/shipping/purolator-specialized-services/dangerous-goods/limited-quantity-exemption

UPS, “Limited Quantity Exception – Ground Service,” https://www.ups.com/us/en/help-center/packaging-and-supplies/special-care-shipments/hazardous-materials/ground-limited.page

United States Postal Service, Publication 52, Hazardous, Restricted and Perishable Mail, https://pe.usps.com/text/pub52/welcome.htm

ICC The Compliance Center, “Shipping Limited Quantities by Ground vs Air, What’s the Difference?” https://www.thecompliancecenter.com/ca/shipping-limited-quantities-by-ground-vs-air-whats-the-difference/

ICC The Compliance Center, “What Are Excepted Quantities?” https://www.thecompliancecenter.com/ca/what-are-excepted-quantities/

Stay up to date and sign up for our newsletter!

We have all the products, services and training you need to ensure your staff is properly trained and informed.

Limited Quantity Label, 4″ x 4″, Gloss Paper, 500/Roll |

Excepted Quantity Label, 4″ x 4″, Gloss Paper, 500/Roll |

Repacking Services |